The Indonesian island of Lombok, sits within the much storied “Ring of Fire”, a volcanic arc that stretches some 40,000 km in a horseshoe shape around the Pacific Ocean. The island itself lies on the boundary between two tectonic plates (Australian and Sunda) and, unlike neighbouring Bali, which has been has been forced up from the ocean floor due to subduction – ie the Australian plate pushing up beneath the Sunda plate, Lombok has been formed, almost entirely, by successive layers of volcanic matter built up over a period of around 10 million years.

Lombok island has been formed as a result of volcanic activity taking place over millions of years.

Despite being rocked by a spate of major earthquakes over a five-week period in 2018, seismic activity has been relatively subdued on Lombok in the modern era.

Prior to 2018, only seven earthquakes have been recorded since 1865 with a magnitude greater than 6.

Mt Rinjani, an active volcano in the island’s north, has erupted 12 times over the same period but has only once been considered “severe”- ie an eruption with a VEI (Volcanic Explosivity Index) over 2.

By comparison, the ancient Mt Samalas, which once stood alongside Rinjani, erupted in 1257 AD with a VEI of 7 and is considered to be one of the largest volcanic eruptions of the last 7,000 years.

While the island ‘s geology reveals many details about it’s origins the history of it’s indigenous inhabitants, the Sasak, remains more of a mystery.

Although it is well known that early humans migrated to South East Asia, spreading throughout Indonesia and arriving as far south as Australia up to 60,000 years ago, the ancestors of Lombok’s modern-day inhabitants, the Sasak, arrived during a much more recent migration, that of the Malay race and probably within the last 3 or 4,000 years.

Given that earlier human races had been moving eastwards from Bali well before then, it is entirely possible that Lombok was already inhabited at the time of the Sasak’s arrival.

There are however, no oral, written or archaeological records to confirm this, so it is unknown who, if anyone, the Sasak may have encountered on their arrival or how the two groups might have interacted.

What is known is that the early Sasak people were farmers whose community and spiritual life centred around animist beliefs and ancestor worship. Sasak communities also spread into neighbouring Sumbawa, however early Sasak culture appears to have evolved in isolation for many centuries with little known interaction between the Sasak and their neighbours in Bali and Java.

Descendants of this tribe from the north of Lombok, known as “Sasak Boda”, still follow the animist traditions of their ancestors.

Descendants of this tribe from the north of Lombok, known as “Sasak Boda”, still follow the animist traditions of their ancestors.

Beyond this, there are only two recorded references to Lombok prior to the 17th century AD.

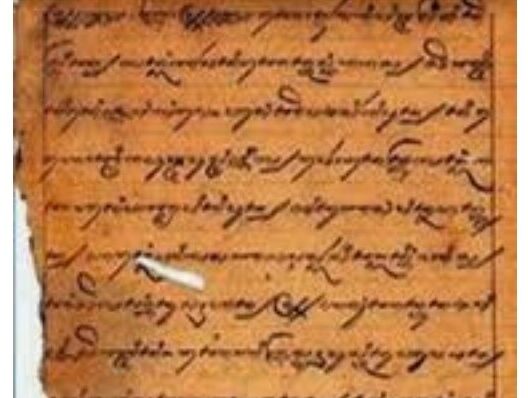

The first is the “Babad Lombok”, a 13th century manuscript written on palm leaves in Old Javanese.

This document is an eye-witness account of the 1257 eruption of Lombok’s Mt Samalas. (Also known as “old Rinjani”,

Mt Samalas stood 4000 metres above sea level alongside present day Mt Rinjani.) The Babad Lombok records that lava flows from the eruption buried large parts of Lombok including the ancient capital of Pamatan, which to this day lies undiscovered, buried under volcanic rock somewhere on the island.

Lava flows also crossed the sea and wiped out part of western Sumbawa. Molten rock ejected from the mouth of the volcano reached as far as Bali and Sumbawa. Ash deposits 3 cm thick settled on Mt Merapi in Central Java.

The eruption was so severe that it is said the affected areas on all three islands remained barren and uninhabited for generations.

Whatsmore, the force of the eruption literally caused the volcano to “blow it’s top” and what is left of Mt Samalas today can be seen standing at half it’s original height in the form of the caldera, Lake Segara Anak.

Lake Segara Anak, with Mt Rinjani in the background is all that remains of the once mighty Mt Samalas

Lake Segara Anak, with Mt Rinjani in the background is all that remains of the once mighty Mt SamalasScientific research conducted as recently as 2013 concluded that the eruption was possibly the largest volcanic eruption of the last 7,000 years.

Eight times more powerful than the eruption of Mt Krakatoa, it is estimated that 40km3 of volcanic matter was projected up to 40km into the atmosphere and not only disrupted weather patterns and temperatures around the world for several years but contributed to crop failures, drought and famine as far away northern Europe and Africa.

The scientists that tied existing geological evidence of such an eruption to the Samalas volcano noted that to find the lost city of Pamatan would be the equivalent of discovering Pompeii.

The second, far less dramatic account, is a reference made in a 14th century document, “Nagrakretagama” which noted that “Lombok Mirah” was an island under the jurisdiction of the Majapahit Empire, the most powerful Javanese Hindu Kingdom of the day.

The Majapahit Empire in fact assumed sovereignity of most of the islands that make up present day Indonesia, however direct administration of the empire did not extend beyond Bali and as a result, Javanese Hinduism was not adopted in Lombok in any meaningful way.

Similarly, in the 16th century, a Sasak prince’s efforts to introduce Islam to the island’s inhabitants was not embraced to the same extent as in neighbouring Java.

Rather, elements of both Hinduism and Islam have been woven over time into the native Sasak’s existing beliefs and have evolved into a synthesized religion known as “Wetu Telu.”

A traditional dance and music performance featuring the “gendang beleq” or, big drum.

A traditional dance and music performance featuring the “gendang beleq” or, big drum.

One of the most detailed and insightful accounts of Lombok island came in the 19th century from English naturalist, Arthur Russel Wallace in his seminal 1869 work, “The Malay Archipelago”.

During his many years cataloguing and recording flora and fauna across the length and breadth of Indonesia, Wallace was the first person to correctly observe that while the islands of Indonesia appear to have once been part of a single land mass there are in fact two distinct biological zones, associated with the two converging continental shelves.

Hence, the islands to the west of Lombok bear the flora and fauna of their South East Asian neighbours, whereas Lombok and all the islands to the east bear physical characteristics and animal species more closely associated with Australia.

Although the distance between Bali and Lombok is only 35 kilometres the Lombok Strait has also proven to be an impassable barrier for the migration of land animals, Bali being the furthest point past which no tigers, elephants or Asian rhinoceros have crossed.

Similarly, Australian marsupials and other wildlife, many species of which can be found in eastern Indonesia, have not migrated west beyond the shores of Lombok.

Now commonly referred to as the “Wallace Line”, the other consequence of this biogeographic divide is that even though Lombok has distinct wet and dry seasons typical of equatorial regions, Lombok receives less rainfall than Bali and is generally less humid.

The Wallace line notes a deep sea trench which runs between Bali and Lombok which in turn marks a biogeographic boundary between South East Asia and Australia

The Wallace line notes a deep sea trench which runs between Bali and Lombok which in turn marks a biogeographic boundary between South East Asia and AustraliaPrior to the 17th century Lombok was made up of numerous competing fiefdoms, each ruled by a Sasak prince. But by the time Wallace arrived in Lombok in the mid-19th century, the Balinese had indeed crossed the geo-divide and the Sasak were firmly under Balinese rule.

The rise of Islam throughout Sumatera and Java during the 16th century had forced many Javanese to flee to Bali and, as the last stronghold of Hinduism in Indonesia, it appears that conquest of the islands to the east was the obvious way for the Balinese to consolidate power.

The Balinese invaded western Lombok early in the 17th century and although the Makassarese people of Sumbawa invaded eastern Lombok around the same time, by 1750 the Balinese controlled the entire island.

During this era the Sasak system of village government remained in place but village heads became little more than tax collectors for the Balinese and the Sasak aristocracy lost much of its power.

Infighting amongst the Balinese however, resulted in the island being broken up into four feuding kingdoms until 1838, when the kingdom of Mataram, under the rule of Anak Agung Ngurah Karangasem brought the three other kingdoms under its control.

King Karangasem was said to be a wise ruler and relations between Hindus and Sasaks in the western part of the island are said to have been largely harmonious and intermarriage was not uncommon.

In the east however, the Balinese ruled from garrisoned forts and Sasak uprisings were a regular occurrence.

After one such uprising Sasak chiefs sent an envoy to the Dutch in Bali and invited them to rule. The Dutch governor General signed a treaty with the Sasak rebels in 1894 and sent a large army to Lombok.

The Balinese raja capitulated but a group of young princes chose to fight on and a series of bloody battles ensued.

The Dutch army however, was too strong and Mataram was forced to surrender. The entire island was annexed to the Netherlands East indies in 1895.

The Dutch ruled the islands 500,000 inhabitants with a force of 250 soldiers by cultivating the support of both the Balinese and Sasak aristocracy.

Although there are reports of a punitive tax regime and slave like treatment of villagers, the Dutch are widely remembered as liberators from Balinese oppression.

The Japanese sailed into Ampenan Harbour on March 9, 1942 and are said to have quickly overwhelmed the Dutch and taken control of both the port and the island.

Control was temporarily returned to the Dutch following the end of WW2 but following Indonesia’s independence in 1945, the Balinese and Sasak aristocracy were returned to their former seats of power.

Following the coup attempt on Indonesia’s first president, Soekarno, mass killings of Chinese and suspected communists occurred in Lombok, consistent with what happened during that time across the archipelago.

After the rise to power of President Suharto in 1967 Lombok experienced a degree of stability but the economic benefit was not as pronounced as it was in Java and Bali.

Crop failures led to famine in 1966 and mass food shortages in 1973.

The Suharto Government’s “transmigrasi” program moved a lot of people out of Lombok during this time.

Developers and speculators instigated a mini tourist boom in the early 1980’s however the locals share of earnings was limited.

Indonesia’s subsequent political and economic crises of the late 1990’s have had a pronounced impact on the islands fortunes.

In early 2000 riots broke out in Mataram with extremists being blamed for inciting anti-Christian and anti-Chinese sentiment supposedly in retaliation for sectarian violence that was being perpetrated against Muslims in the Mollucan islands.

Authorities immediately cracked down on trouble makers however unrest quickly spread to neighbouring Sulawesi. Rumours of imminent riots in Jakarta and other Javanese cities also began to circulate, causing some to suggest that there may have been a wider campaign to destabilise the country by a group of people who had lost power during the government’s recent transition to democracy.

Despite still struggling to overcome the physical and economic impact of the 2018 earthquakes, Lombok today enjoys the stability that has come with Indonesia’s successful transition to social democracy.

The islands 3.5 million inhabitants are predominantly Muslim with smaller numbers of Hindus as well as some communities who still practice traditional Wetu Telu beliefs.

Although tourism has not developed to the same extent that it has in Bali it is nevertheless, Lombok’s largest industry, followed by gold and copper mining, agriculture and fishing (including the pearling industry).

The challenge ahead is to meet the needs of economic development with proper management of the islands natural resources and to provide modern facilities and infrastructure for the islands 3.5 million inhabitants while taking care to preserve the traditional customs and lifestyle still being practiced to this day.

It is indeed a history being written as we watch.